Fetching your location...

bristol, uk >>> amsterdam, nl

| blue ballpoint | |

| Year | 2024 |

| Media | bic blue biro, ink, screenprint, knitted socks |

| With | auntie ann |

blue ballpoint & knitted socks

for the ‘correspondences’ edition of @r_o_b_i_d_a, i wrote with my 86 year old auntie ann this essay about the bic biro. it was a text about the uncanniness of proximate objects, and a previous project at dae that materialised the 2km of ink per pen boasted by the infamous ballpoint. in the letters exchanged with auntie ann for the text, she remained steadfast in steering off-topic from the pen, adding stories about time spent with family, and offering to knit small gifts for friends and i. throughout the years, random parcels full of these cosy treasures have arrived with her reciprocal writing, including the latest parcel of a dozen bed socks now spread among babes throughout amsterdam. this text and my aunt’s knits have become even more important of late. to the lucky bbs who are warmed by her cosy socks or own a legendary pair of 7-finger gloves, know how special and loved u are x

text edited with @aljazskrlep

& extended thanks to @vidarucli x

The iconic blue ballpoint BiC Cristal pen boasts two kilometres worth of ink. That’s two thousand centimetres of scribble: exchanges, recipes, thoughts and updates. At least that’s what Auntie Ann and I use our letters for, back and forth between Bristol where she is, and me, in Amsterdam.

Our letters travelled approximately 720 km – 360 BiC pens. She cannot visit Amsterdam due to old age, and I only manage to visit perhaps twice a year. As such, our letters offer a physicality to our relationship during these between periods - feeling the soft wrinkles of her palm through her scribe - reducing the gap between us.

A pen’s thinghood establishes a passive guise. It is an object that is banal and commonplace,easily disposed of or forgotten about in the chaos of the junk top-drawers of an office or home. Yet, there’s a paradox ink the value held by the ink within such a seemingly passive object: the power of a signature, the pleasure of a note, the significance of a written letter.

I don't think at the time I was your age people hadn't been as conscious of saving the planet as they are now. So I don't believe my input will help an awful lot. Anyway we probably making more damage to the planet by using batteries and electricity with using computers and things to communicate with.

In her initial reply, Auntie Ann wrote of batteries and electricity as more greatly impacting the planet when considering the ways in which we as humans communicate. Understandably a pen as an object, compared to the vastness of underwater cabling, and the great scales of the internet to someone of her generation with fewer years and use of digital means, are quite incomparable. Perhaps in not wishing to form statements if true or false, this comparison by Auntie Ann instead addresses the phenomenological aspect of communication today. Where I, a 28-year-old writing to my aunt, think about how strange the scale of written ‘analogue’ letters feels travelling across countries and thinking about lengths of ink, whereas for Auntie Ann, a 86-year-old writing to her niece, it is curious to understand the connections made via email or through other digital means.

Sara Ahmed writes, “It is not just that bodies are moved by the orientations they have; rather, the orientations we have towards others shape the contours of space by affecting relations of proximity and distance between bodies. Importantly, even what is kept at a distance must still be proximate enough if it is to make or leave an impression.”1

I realised that to position a pen as an estranged or uncanny object for Auntie Ann was difficult. For her, a pen was familiar. Much more so than the digital writing tools I am using daily. Its proximity was attached to her body’s knowledge in a long standing relationship.

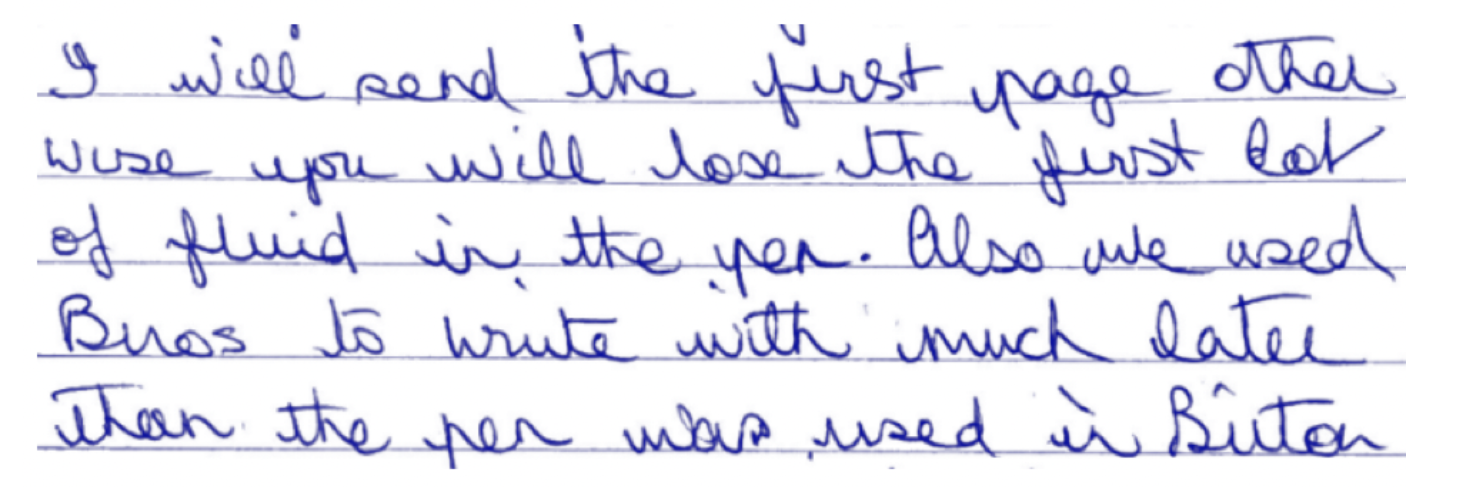

I will send the first page other wise you will lose the first lot of fluid in the pen. Alo we used Biros to write much later than the pen was used in Britain.

She had written with pens since she was a child, though had noted to have used the biro not until later in her years when it was more popular (thanks to Bich and his aforementioned mass-manufacturing). Impressions of the pen had been left on Auntie Ann’s body, too, as a woman writing to loved ones far away. The familiarity of those she dearly cared for recorded through traces of familiar matter; ink and intimacy blotting into one another,reducing the gap between distanced kin, such as my Uncle Graham, Auntie Ann’s husband, when he had served in the navy in the 1950s and 1960s.

Perhaps then, it is the pen’s link to domesticity that inscribes it as so familiar to my aunt. As a CIS female body whose formative years were spent taking care of her family in the post-WWII period, writing letters brought others into the proximity of home with a closeness to their body that could not be offered in the ways we know now via FaceTime, or as readily through phone calls. Moreover, the many hand-written recipes or shopping lists my Auntie Ann has written throughout her years further entangles the use-value of the pen with domesticity, and that of the female’s role in the home during this period. Judith Butler’s thoughts on “Materia [which] denotes the stuff out of which things are made… as extensions of the mother’s body,” 2 furthermore makes a correlation between the assumed labour and care of a female-figure, and the forgotten ink in and amongst its written sentiment.

As such, the sensation of an ongoing paradox between closeness and distance in letter writing - the ink travelled and marks made - is the very thing that maintains the pen as an object-away. The sentiment and affections embodied in the ink allow the pen to step backwards. Its value remains in the loops and dots and crosses of its words. And so, the pen remains an abstraction, whilst the ink persists as sensual, each unique yet together hidden in their domesticity, amongst the good wishes and family mentions:

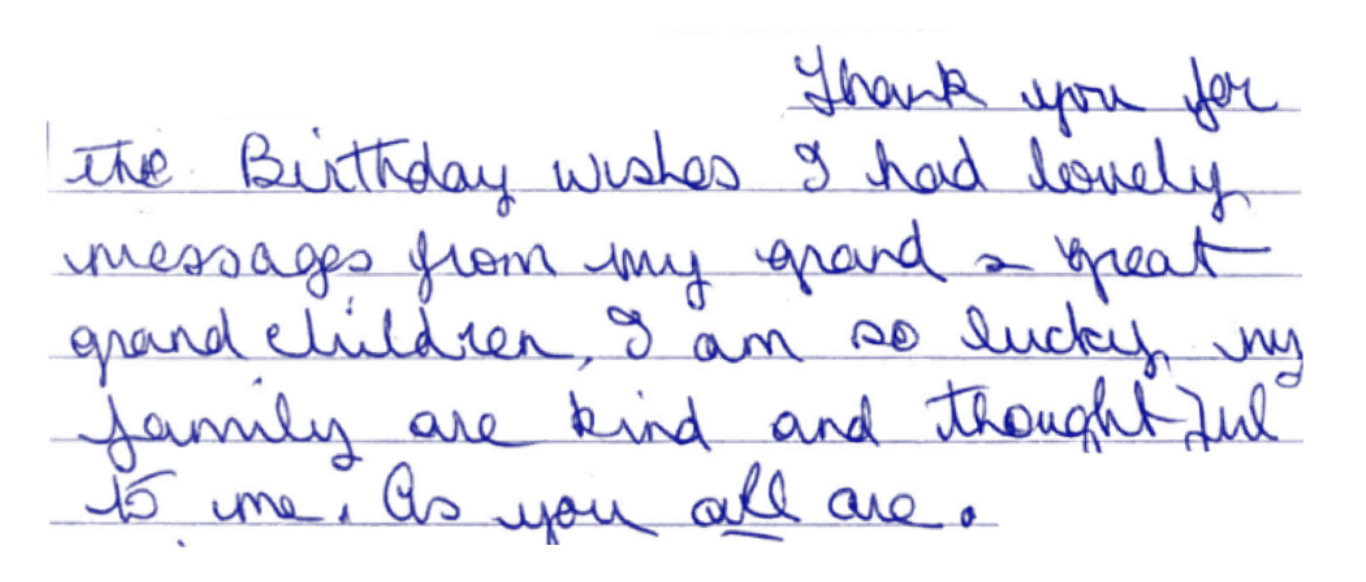

Thank you for the Birthday wishes I had lovely messages from my grand & great grand chiliden. I am so lucky, my family are kind and thoughtful to me. As you all are.

In its registries as an object all-at-once neither here, nor there, the BiC Cristal ballpoint takes on a local manifestation of what Timothy Morton names a hyperobject. 3

So vastly spread in its temporal and spatial awareness in relation to its observer(s), the term has typically been affixed to ‘global warming’ or ‘climate change’, though also attached to the likes of matter such as Styrofoam. Stuff that at a given moment can be touched and understood at the scale in which it is present then, though does not offer a sense of the fourteen million tons produced each year. 4 In the very same way this text is stained in pursuit of the scale of a single pen, a hyperobject confronts the concurrent proximities and distances imbued in a single item.

If the hand of the scribe is considered the seismograph, is the ink the quake?

The inter-objective quality of a pen is not only then in its exchanges between paper and person. It is a contemporary object made of mined tungsten, crude-oil turned polymer, and crystal violet and Prussian blue pigment intra-acting with flesh and atmosphere. In its position away, it's transcorporeal 5 body is historic in the memories it writes, as well as the bodies with whom it is produced- and made-by as commodities.

In a world where “there is no Away”, 6 the 150 billion BiC Cristal pens, if not aloof in the back of the junk drawer, exist and degrade without a seemingly perceivable trace. Ahmed’s thoughts on Queer Phenomenology and the notion of “(re)orientation" 7 previously quoted, shed light on how the entanglement of body and object “apprehend this world of shared inhabitance, as well as “who” or “what” we direct our energy and attention toward”. 8 What would it then be like to confront oneself with 2 km of ink in a given moment? The exercise with which this text started in writing back and forth with my Auntie Ann might have even exasperated the phenomenological feeling I hoped to reduce. The pen, now empty, has brought her thoughts closer to me through the total of four letters (still, to say, with a small amount of ink to spare - at a guess 500 cm?), with the legibility of that 2 km as a whole to remain at a loss.

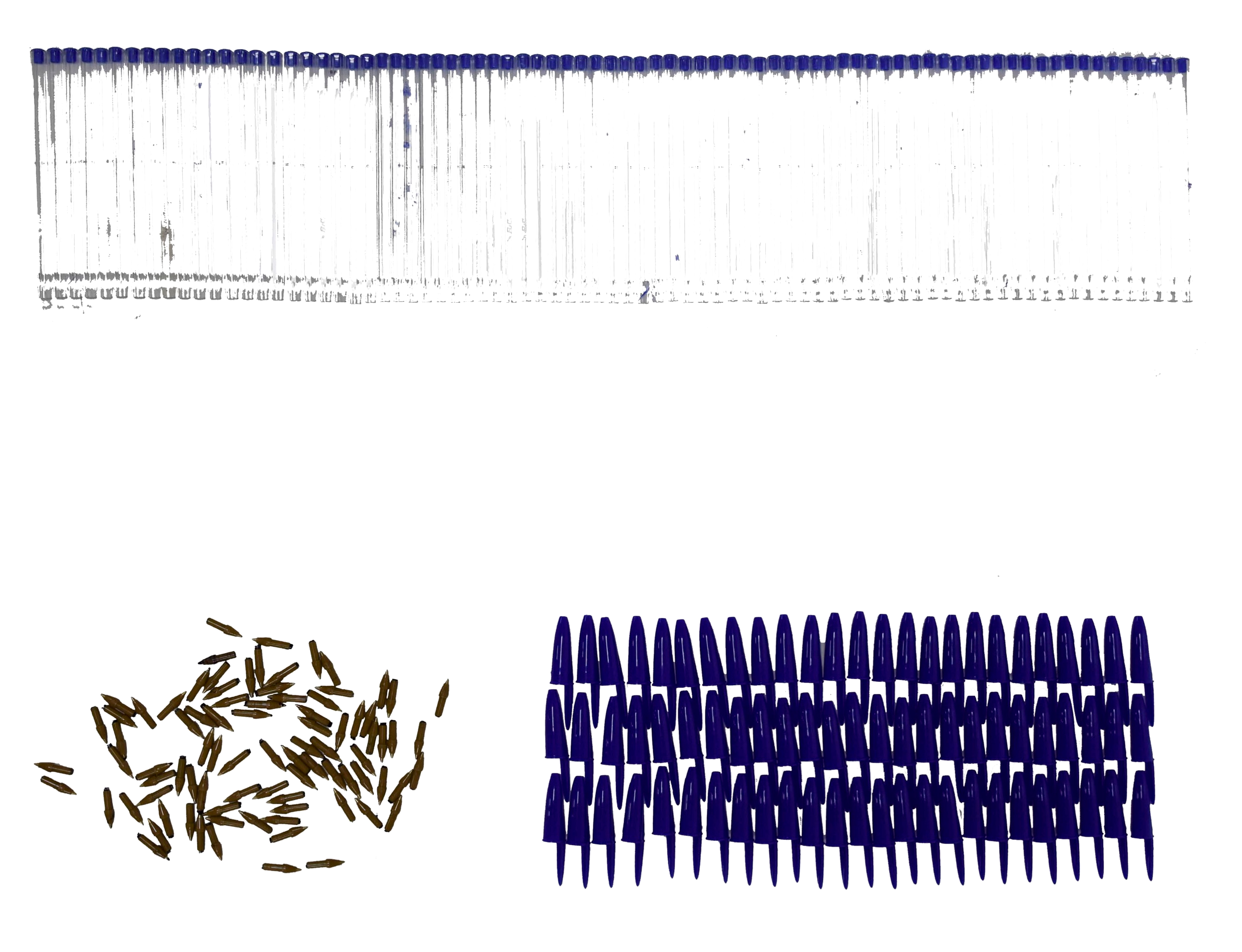

Towards a less enigmatic relationship with the BiC Cristal ballpoint pen, I will say this is not my first attempt. In 2021, I produced a project entitled The Blue Ballpoint. In the same way in fixating on what one pen’s worth of ink felt, or looked, or smelt, or performed like - to know it at one moment, in a singular time and place - I screen printed a BiC Cristal 180 cm diameter circle. An attempt at a printed namesake to its 2 km line counterpart.

In a way, I had to know the scale through the matter itself. The ink could not take on the guise of prose, letter, or recipe. I wished to reside just with the ink, even if for a short while…

In producing the work I found an uncanny kinship between the blue ballpoint and its ink as a round large azure mass, with the 1972 image of The Blue Marble. In its hope of a new perspective of Earth - to be finally seen as a whole - Apollo 17’s iconic image was named “the most environmental photograph ever taken”. 9 Far from it, in his lecture titled Inside, 10 Bruno Latour notes the issues arising from such imagery that rather than creating a unity, in fact, enlivened the fraternal natures of man’s gaze on the planet.

“The view from outside” 11 was marbled with “the view from God”, 12 allowing this feeling of other and distance to prevail. To return to Ahmed, “Moments of disorientation are vital”. The unsettled or eerie connections produced by an endeavoured totalitarian view of a planet, or even holistic reading of pen ink, perhaps should remain curious. Presented in the singular pause I had honed for, it was displaced from the sentiment I adored when seeing the matter within a letter from Auntie Ann.

In many ways, it did offer satisfaction to see the ink at a given time. Yet thanks to Bíró’s sticky formula of ink perfect for oozing over the suspended metal ball, it had meant that retrieving enough ink for the print from a single pen was impossible. In the end, I had used over 200 pens to collect the amount of ink needed to screen print the circle. The distance was now 400 kilometres, not two.

In hopes of a “neo-local representation” of the BiC, the goal was to arrive at an aesthetic that could reduce its phenomenological and pervasive thinghood. I wished for an intimate understanding of what this cheap and mass-produced object offered beyond itself. Though, if honest, it had always been there. It might not be in the scale as direct as a 2 km line that affords me an understanding of the pen. But rather, just to let it be in close proximity, simply aware of the fact that I won’t understand it ever as a whole, nor will it of me, nor will anyone/thing of anything/one; “…each impression is linked to the other, so that the object becomes more than the profile that is available in any moment.”

In reducing ink to singular stuff I must reflect on my own understanding of its matter and materiality as something much more in flux. On the large scale of the hyperobject, ink remains a collective. It is made larger than the stuff itself within my pen, though in light of Ahmed’s comment, I laminate it with Astrida Neimanis who states that “matter repeats, but always differently”.

To know the pen and its ink should not be about trying to do so from one singular perspective. To look beyond The Blue Ballpoint with the same positionality as those imagining they can capture The Blue Marble, imagining one can do so to see a whole, is to know something through its presenting and untraceable means, finding the multitudes that remain inconsistent, and embrace them. Likely, it may sound over the top to endeavour such a queered reading of a commonplace biro pen. In its guise as much more than simply ink, the links between letters surpassed the “fluid in the pen”, rightly so losing the interest of Auntie Ann early on. What in fact persists is the need to find connection, even at a difference.

Ultimately, we lost track of the task at hand and enjoyed our usual exchange on her recent birthday celebrations and times with family. The care and joy stained amongst the ink in our letters. I cherish greatly the letters I receive from Auntie Ann, and in losing track of where the pens that have written our correspondences may now reside, hold tightly onto their ink in their guise as letters, congealed with paper and impressions.

As she always does, Auntie Ann made sure to offer her way of connection through the ways her writing-hands know best:

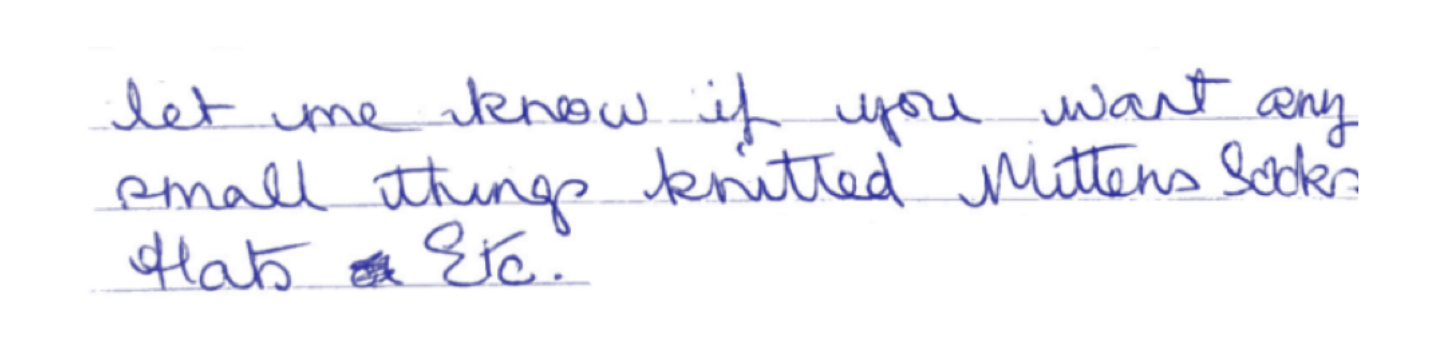

Let me know if you want any small things knitted. Mittens, socks, hats, etc.

Footnotes

- Sara Ahmed. 2006: Queer Phenomenology. Durham and London: Duke University Press, p. 159. <

- Judith Butler. 1996. Bodies That Matter: On The Discursive Limits of Sex. Routhledge Classics, p. 41. <

- Timothy Morton. 2013: Hyperobjects: Philosophy And Ecology After The End Of The World. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press. <

- Morgan Meis. 2021: “Timothy Morton’s Hyperpandemic”. The New Yorker, accessed 13 June 2024, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/persons-of-interest/timothy-mortons-hyper-pandemic <

- As defined by Stacy Alaimo in Stacy Alaimo. 2008: “Trans-corporeal Feminisms and the Ethical Space of Nature”. In: Stacy Alaimo and Susan Hekman. 2008: Material Feminisms. Indiana: Indiana University Press, p. 238. Transcorporeal means “time-space where human corporeality, in all its material fleshiness, is inseparable from “nature” or “environment”.” <

- Timothy Morton. 2013: Hyperobjects: Philosophy And Ecology After The End Of The World. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, p. 31. <

- Sara Ahmed. 2006: Queer Phenomenology. Durham and London: Duke University Press, p. 2. <

- Ibid., p. 3. <

- William Anders. 1968: “Earthrise”, December 24. Land and Lens: Photographers Envision The Environment. <

- Bruno Latour. 2018: INSIDE, Performative Lecture with Zone Critique, accessed 13 June 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gzPROcd1MuE&list=PLb8eIfP2zr1-2Vk_Fmqr8JpqAEJ008dks&index=8 <

- Ibid. <

- Ibid. <